Phytochemical Profiling and in vitro Assessment of Annona muricata L. Leaf Extracts for Antioxidant and Antibacterial Propertie

| Received 04 Nov, 2025 |

Accepted 01 Feb, 2026 |

Published 10 Feb, 2026 |

Background and Objective: Annona muricata L. is known for its rich diversity of secondary metabolites, yet limited data exist on the comparative bioactivity of its solvent-based leaf extracts. This study aimed to evaluate the phytochemical composition and assess the antioxidant and antibacterial properties of acetone and methanolic leaf extracts of A. muricata. Materials and Methods: Leaf phytocompounds were extracted using acetone and methanol. Functional groups were identified through FTIR-ATR, while phenolic and flavonoid contents were quantified using HPLC. Phytochemical profiling was further conducted using ESI-MS. Antioxidant activity was evaluated using DPPH and FRAP assays, and antibacterial activity was assessed against four human pathogenic bacteria using the agar well diffusion method. Statistical analyses were applied to compare extract performance across assays. Results: The FTIR confirmed the presence of phenolic and carboxylic functional groups in both extracts. HPLC analysis revealed phenolic and flavonoid compounds, with coumaric acid detected at 57.95 mg/g in the acetone extract and 52.85 mg/g in the methanol extract. The ESI-MS identified Octadecane, 1-(ethenyloxy)- as the major compound in the acetone extract and Cholesta-5,7,9(11)-trien-3-ol acetate in the methanol extract. Antioxidant assays showed higher activity in the acetone extract, with a DPPH IC50 value of 105.43±5.94 μg/mL. The acetone extract at 75 μg/mL exhibited the strongest antibacterial effect, producing a 9±0.04 mm inhibition zone against Salmonella typhi. Conclusion: The study demonstrates that acetone leaf extracts of A. muricata possess superior antioxidant and antibacterial activity compared to methanolic extracts. These findings support the potential application of acetone-extracted phytocompounds from A. muricata in natural antioxidant and antimicrobial formulations. Future research should explore compound isolation and mechanism-based evaluations.

| Copyright © 2026 Prakasa et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

The vast and varied ecological landscapes in India offers richest biodiversity with diverse medicinal and aromatic plants species. These diverse medicinal plant varieties contribute to the availability of natural bioactive compounds with great significance to nurture the human health1. Natural compounds from medicinal plants have long been used for drug discovery with diverse therapeutic potential2. Globally, the traditional medicinal system has relied on plant-based remedies as therapeutic agents for both physical and mental health issues3. Recent studies have highlighted that plant secondary metabolites such as phenolics, alkaloids, saponins, and terpenoids have emerged as promising antibacterial agents4. The chemical diversity of the drugs obtained from medicinal plants possess synergistic activities such as antibacterial, antiviral, antiprotozoal and antioxidants. Since, the drugs obtained from medicinal plants are cost-effective; there exists create great demand for these drugs in the market with minimal side effects than synthetic drugs5. The use of herbal medicines in future therapeutic applications relies on complementing clinical data with real world evidence and outcome measures6.

Annona muricata is a tropical evergreen hat reaches a height of 5-6 m and belongs to the Annonaceae family. The leaves, bark, fruits, and roots of A. muricata are employed in traditional herbal remedies. Notably, the fruit and leaves are valued for their tranquilizing and sedative effects. Traditionally, decoction of A. muricata leaves is used as a pain reliever and for treating gall bladder ailments. Externally, the leaves can be applied to alleviate eczema, skin rashes, and swelling. In addition, topical application of A. muricata leaves is believed to accelerate wound healing and prevent infections. In herbal medicine, A. muricata fruits are utilized to alleviate joint pain, treat heart conditions, act as a sedative, and mitigate coughing or flu symptoms7. The roots and leaves of A. muricata have higher phenolic contents. The medicinal and pharmacological potential of A. muricata has led to its investigation as an alternative therapy for bacterial infections, diabetes, hypertension, and cancer8. Also, for pest control and insect repellent purposes, the parts of A. muricata plant, including its unripe fruit are used as natural alternatives to synthetic chemicals9.

Since various plant parts of A. muricata finds its use in ethnomedicinal practices, the current study deals with phytochemical profiling of acetone and methanol leaf extracts of A. muricata using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) analytical techniques. Furthermore, in vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of A. muricata leaf extracts will be evaluated against four human pathogenic bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area and duration: This research work was carried out in Vilar, located in the Thanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India, during the time period of 2022 to 2024.

Chemicals and reagents: Chemicals and reagents used were analytical grade, purchased from Hi Media Laboratories Pvt Ltd., Mumbai, India. The solvents and synthetic compounds were obtained from S.D Fine Chem Ltd., and Sigma Aldrich, respectively.

Plant sample collection: Annona muricata L. leaves collected from Poondi, Thanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India. Taxonomical identification, confirmation and certification were provided by Bharathi herbarium in the Department of Botany, Bharathiar University, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India (Ref no: (BU/DB/25/23/2021/Tech./1054) by characteristic identification and compared with the type specimen depository in the herbarium.

Extraction of phytocompounds using the soxhlet method: The collected fresh leaves were washed with tap water to remove the dust particles and again washed with distilled water. The cleaned leaves were dried at 40°C using hot air oven and powdered using a mechanical blender. About 20 gm A. muricata leaf powder was extracted successively with organic solvents namely acetone and methanol using Soxhlet apparatus. The crude acetone and methanolic leaf extracts concentrated using a rotary evaporator and stored at 4°C after complete evaporation of the solvents10.

Analytical characterization of leaf extracts

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR-ATR) analysis: The phytocompounds were extracted from A. muricata leaves using acetone and methanol solvents were characterized using FTIR-ATR spectroscopy. About 5 mg of leaf extract was analysed in the spectrum range from 4000 cm to 600 cm. The functional groups were analysed using the peak values.

High performance liquid chromatographic analysis: Both acetone and methanol leaf extracts of A. muricata were subjected to HPLC analysis (Shimadzu, Japan) for the determination of phytocompounds. A C18 column coupled with a PDA detector and a mobile phase containing water and methanol with a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min for 60 min was used for phytocompound separation. The column oven temperature was 40°C. The synthetic compounds, namely coumaric acid, rutin, catechin, and quercetin, were used to identify the presence of bioactive compounds in leaf extract by comparing retention times of both synthetic compounds and leaf phytocompounds. The retention time of synthetic compounds were detected using our previous results11.

Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry Analysis (ESI-MS): The fingerprinting of acetone and methanol leaf extracts was performed using ESI-MS analysis. The temperature, capillary voltage and cone voltage were set to 100°C, 3.0 kV and 40 V, respectively. The ESI-MS was performed by direct infusion of the sample with a 10 μL/min flow rate using a syringe pump. Mass spectra were accumulated over 60 sec, and the spectral range was obtained between 10 and 500 m/z12.

Antioxidant activity of leaf extracts

DPPH radical scavenging activity of extracts: DPPH activity of A. muricata acetone and methanol leaf extracts was determined according to Blois13. About 100, 200, 300, 400 and 500 μg/mL of leaf extracts were added to 5 mL of 0.1 mM methanolic DPPH solution and incubated at 27°C for 20 min. About 0.1 mM DPPH methanolic solution served as a negative control. Blank used was methanol. The DPPH, methanol, and ascorbic acid were the positive control. Sample absorbance measured at 517 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Inhibition percentage of extracts was calculated by following the equation:

Ferric reducing antioxidant power assay: The FRAP assay performed for both acetone and methanol leaf extracts of A. muricata according to the method of Pulido et al.14. The reagent containing 20 mM 2,4,6-tris (2-pyridyl)-s-triazine (TPTZ) and FeCl3 (20 mM) was prepared in 0.2 M acetate buffer and added to the samples. Rutin served as a positive control. The samples were incubated for 30 min at 37°C, and blue color absorbance was measured at 593 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. The reducing power ability was expressed as antioxidant concentration with ferric-TPTZ reducing ability equivalent to 1 mM FeSO4·7H2O.

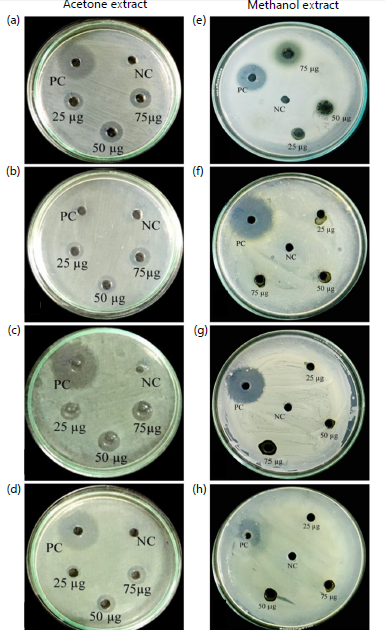

Antibacterial activity of A. muricata leaf extracts: The antibacterial effect of A. muricata leaf acetone and methanol extracts was analyzed against four bacteria belonging to the human pathogenic group, namely Salmonella typhi, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Bacillus subtilis by agar well diffusion method. The suspension culture at 103 cfu/mL concentration was loaded and swabbed on a nutrient agar plate. Then, different concentration of each extract (25, 50 and 75 μg/mL) was added into 6 mm diameter wells in agar plate. The positive control was chloramphenicol, whereas acetone and methanol were negative controls. These plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hrs. The inhibition zone around wells were observed and recorded15.

RESULTS

Analytical characterization of leaf extracts

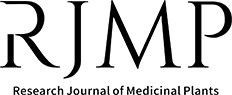

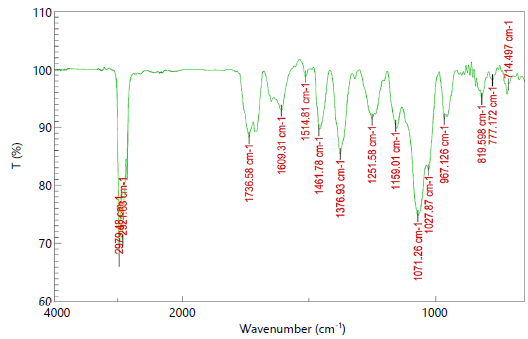

FTIR analysis: The functional groups present in acetone and methanol leaf extracts of A. muricata were determined using FTIR-ATR in 4000/cm to 650/cm range (Fig. 1 and 2).

Almost similar functional groups were analysed in both acetone and methanol extracts and the results revealed intense peaks in spectrum that indicated existence of functional groups. The functional groups of lipids, proteins and cell wall components were observed in both the extracts. The acetone extract showed strong intense peak at 2979.48/cm, indicating the O-H stretching of carboxylic acid. The conjugated anhydride, conjugated alkene, nitro compound, alkane, aromatic ester and sulfonic acid stretching vibrations were observed in the peak ranges of 1736.58, 1609.31, 1514.81, 1461.78, 1376.93, 1251.58 and 1159.01/cm, respectively. Also, the sulfoxide, amine and alkene compounds corresponding to S = O, C-N and C = C bending were also determined in acetone leaf extract (Table 1).

In methanolic leaf extract, the presence of secondary amines and carboxylic acid corresponding to lipid compounds with N-H and O-H stretching vibrations were observed in the peak ranges of 3342.03, 2968.87 and 2922.59/cm, respectively. Also, the amine salt, esters, α, β-unsaturated ketone, nitro compound, alkane, amine alkyl aryl ether and alkenes were observed in the peak ranges from 2852.2 to 718.354/cm (Table 2).

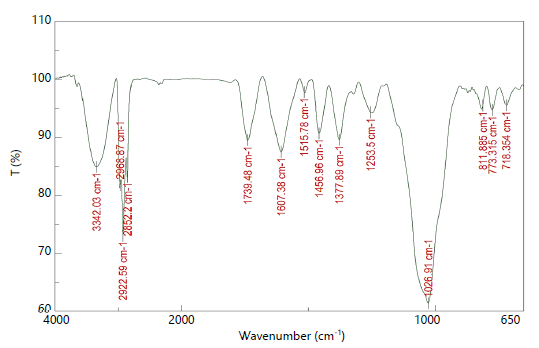

HPLC analysis: The phytocompound analysis of leaf acetone and methanol extracts was performed using HPLC analysis. The peaks of synthetic compounds were compared with our previous results of phenolic and flavonoid synthetic compounds. The chromatogram of both acetone and methanolic leaf extracts of A. muricata showed various peaks in different retention times which indicated different secondary metabolites. Chromatogram of acetone extract showed a characteristic peak at the retention time of RT-4.963, representing the presence of coumaric acid, a phenolic compound. The compound catechin was detected in acetone leaf extract at the retention time of RT-6.475 when compared with synthetic compound. At the retention time of RT-8.385, the compound rutin was detected in the acetone leaf extract. Also, the compound quercetin was detected in acetone leaf extract also at the retention time of RT-13.25 (Fig. 3a). The amount of phytocompounds in crude acetone leaf extract was recorded to be 52.85 mg/g of coumaric acid followed by 24.25 mg/g catechin, 13.25 mg/g rutin and 4.2 mg/g quercetin respectively (Table 3).

|

|

|

The HPLC analysis of A. muricata methanolic leaf extract also exhibited phenolic and flavonoid compounds at the retention times of RT-4.810, RT-6.205, RT- 8.782 and RT-13.623 corresponding to coumaric acid, quercetin, catechin and rutin respectively (Fig. 3b).

The amount of phytocompounds in crude acetone leaf extract recorded to be 57.95 mg/g of coumaric acid followed by 10.05 mg/g catechin, 1.5 mg/g rutin and 2.2 mg/g quercetin respectively (Table 4).

| Table 1: | Functional groups of A. muricata acetone leaf extract analysed using FTIR | |||

| S. No. | Extract absorption (cm) | Functional group | Compound class |

| Lipids (3000-2000/cm) | |||

| 1 | 2979.48 | O-H stretching | Carboxylic acid |

| Proteins (1800-1100/cm) | |||

| 2 | 1736.58 | C=O stretching | Conjugated anhydride |

| 3 | 1609.31 | C=C stretching | Conjugated alkene |

| 4 | 1514.81 | N-O stretching | Nitro compound |

| 5 | 1461.78 | C-H bending | Alkane |

| 6 | 1376.93 | C-H bending | Alkane |

| 7 | 1251.58 | C-O stretching | Aromatic ester |

| 8 | 1159.01 | S=O stretching | Sulfonic acid |

| Cell wall components (1000-600/cm) | |||

| 9 | 1071.26 | S=O stretching | Sulfoxide |

| 10 | 1027.87 | C-N stretching | Amine |

| 11 | 967.126 | C=C bending | Alkene |

| 12 | 819.598 | C=C bending | alkene |

| 13 | 777.172 | C=C bending | Alkene |

| 14 | 714.497 | C=C bending | Alkene |

| Table 2: | Functional groups of A. muricata methanolic leaf extract analysed using FTIR | |||

| S. No. | Extract absorption (cm) | Functional group | Compound class |

| Lipids (3000-2000/cm) | |||

| 1 | 3342.03 | N-H gstretching | Secondary amine |

| 2 | 2968.87 | O-H stretching | Carboxylic acid |

| 3 | 2922.59 | O-H stretching | Carboxylic acid |

| Proteins (1800-1500/cm) | |||

| 4 | 2852.2 | N-H stretching | Amine salt |

| 5 | 1739.48 | C=O stretching | Esters |

| 6 | 1607.38 | C=C stretching | α, β-unsaturated ketone |

| 7 | 1515.78 | N-O stretching | Nitro compound |

| 8 | 1456.96 | C-H bending | Alkane |

| 9 | 1377.89 | C-H bending | alkane |

| 10 | 1253.5 | C-N stretching | Amine |

| Cell wall components (1000-600/cm) | |||

| 11 | 1026.91 | C-O stretching | Alkyl aryl ether |

| 12 | 811.885 | C=C bending | Alkene |

| 13 | 773.315 | C=C bending | Alkene |

| 14 | 718.354 | C=C bending | Alkene |

| Table 3: | Secondary metabolites quantification in A. muricata methanolic leaf extract using HPLC | |||

| Standard | Compound RT (min) | Concentration (mg/g extract) |

| Coumaric acid | 4.81 | 57.95 |

| Catechin | 6.205 | 10.05 |

| Rutin | 8.782 | 1.5 |

| Quercetin | 13.623 | 2.2 |

Hence, these HPLC results suggests that phenolic compounds are more in both acetone and methanolic leaf extract of A. muricata, when compared with the flavonoid compounds.

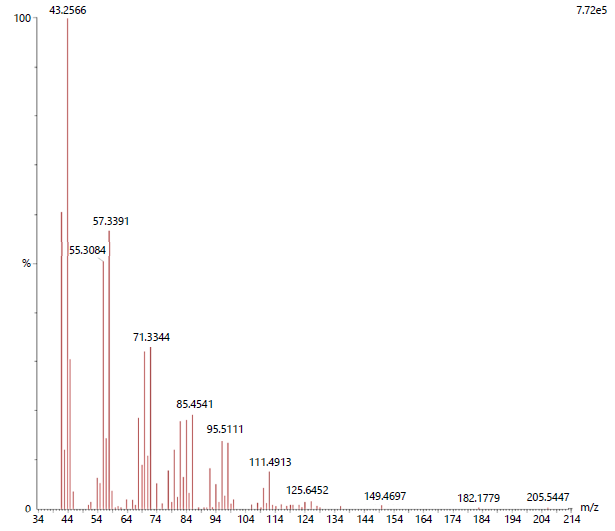

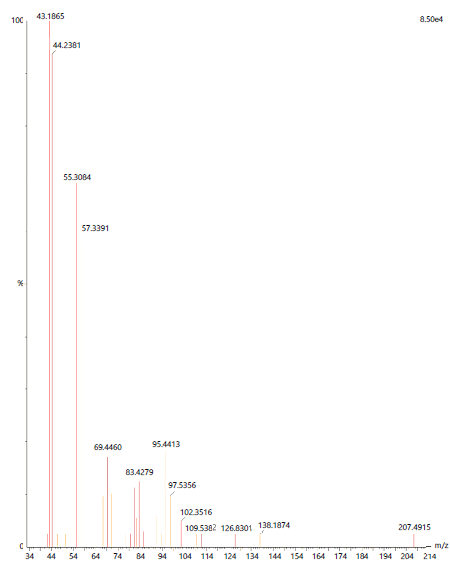

ESI-MS analysis: The electrospray ionization mass spectrum was obtained for the acetone and methanol leaf extracts of A. muricata (Fig. 4 and 5).

| Table 4: | Composition of basal diet fed to Uda rams | |||

| Standard | Compound RT (min) | Concentration (mg/g extract) |

| Coumaric acid | 4.963 | 52.85 |

| Catechin | 6.475 | 24.25 |

| Rutin | 8.385 | 13.25 |

| Quercetin | 13.25 | 4.2 |

|

| Table 5: | Phytocompounds detected in A. muricata acetone leaf extract using ESI-MS | |||

| S. No. | m/z | Compound name | Molecular weight | Molecular formula |

| 1 | 41.9893 | Oxalic acid, allyl pentadecyl ester | 340 | C20H36O4 |

| 2 | 43.2566 | Octadecane, 1-(ethenyloxy)- | 296 | C20H40O |

| 3 | 44.5675 | Oxalic acid, allyl hexadecyl ester | 354 | C21H38O4 |

| 4 | 55.3084 | Oxalic acid, allyl dodecyl ester | 298 | C17H30O4 |

| 5 | 57.3391 | 1-hexacosanol | 382 | C26H54O |

| 6 | 69.9398 | Oxalic acid, allyl undecyl ester | 284 | C16H28O4 |

| 7 | 71.3344 | Oxalic acid, allyl tridecyl ester | 312 | C18H32O4 |

| 8 | 81.3342 | Pentafluoropropionic acid, octadecyl ester | 416 | C21H37O2F5 |

| 9 | 83.4541 | Oxalic acid, allyl octadecyl ester | 382 | C23H42O4 |

| 10 | 85.4541 | Oxalic acid, allyl tetradecyl ester | 326 | C19H34O4 |

| 11 | 92.4959 | Pentafluoropropionic acid, hexadecyl ester | 388 | C19H33O2F5 |

| 12 | 95.5111 | 17-pentatriacontene | 490 | C35H70 |

| 13 | 97.3642 | 2-piperidinone, n-[4-bromo-n-butyl]- | 233 | C9H16ONBr |

| 14 | 110.9786 | Silane, trichlorodocosyl- | 442 | C22H45Cl3Si |

| 15 | 111.4913 | 2-hexyl-1-octanol | 214 | C14H30O |

| 16 | 124.1671 | Heptafluorobutyric acid, n-pentadecyl ester | 424 | C19H31O2F7 |

| 17 | 125.6452 | Hydroxylamine, o-decyl- | 173 | C10H23ON |

| 18 | 149.4697 | Hexatriacontane | 506 | C36H74 |

| 19 | 182.1779 | 1-decanol, 2-hexyl- | 242 | C16H34O |

| 20 | 205.5447 | 1-octadecanesulphonyl chloride | 352 | C18H37O2ClS |

Both the extracts possessed 20 different compound groups. The dominant compound observed in acetone extract was Octadecane, 1-(ethenyloxy)-(C20H40O) with the molecular weight of 296, followed by 1-hexacosanol (C26H54O) and Oxalic acid, allyl dodecyl ester (C17H30O4) with a molecular weight of 382 and 298 respectively (Table 5).

|

In the methanolic leaf extract, the dominant compound was detected to be Cholesta-5,7,9(11)-trien-3-ol acetate (C29H44O2) with the molecular weight of 424. The other dominant compounds observed in the methanolic leaf extract were 9-octadecenoic acid (z)-, 2-(acetyloxy)-1-[(acetylox (C25H44O6), Octadecanoic acid, 2-oxo-, methyl ester (C19H36O3) and 2,6,6-trimethyl-bicyclo[3.1.1]hept-3-ylamine (C10H19N) with the molecular weight of 440, 312 and 153 respectively (Table 6).

In vitro antioxidant activity of A. muricata leaf extracts: The antioxidant potential of both acetone and methanol leaf extracts of A. muricata were analysed by DPPH and FRAP assays. In DPPH assay, the acetone leaf extract showed higher percentage of inhibition of 62.40±2.98% at 500 μg/mL concentration, with IC50 of 105.43±5.94 μg/mL compared with synthetic ascorbic acid (71.71±2.44% of inhibition and IC50 of 21.95±9.95 μg/mL). Whereas at the same concentration, almost similar results were observed in methanolic leaf extract which showed 57.17±5.08 percentage of inhibition with IC50 of 138.42±5.47 μg/mL. The results of FRAP assay also exhibited that acetone and methanolic crude extracts of A. muricata possess increased antioxidant activities, compared to synthetic rutin. The extracts antioxidant activity increased in dose dependent manner in both acetone and methanol extracts. In FRAP assay, higher release of mM Fe(II) equivalents coincides with increased antioxidant activity of test sample. The results exhibited that acetone extract showed 698.17±2.11 mM Fe(II) equivalents per mg extract and methanolic leaf extract of A. muricata exhibited 559.96±1.41 mM Fe(II) equivalents per mg extract when compared with the standard rutin (955.49±2.44 mM Fe(II) equivalents per mg extract) (Table 7).

|

| Table 6: | Phytocompounds detected in A. muricata methanolic leaf extract using ESI-MS | |||

| S. No. | m/z | Compound name | Molecular weight | Molecular formula |

| 1 | 41.9623 | 1,6;3,4-dianhydro-2-deoxy-.beta.-d-lyxo-hexopyrano | 128 | C6H8O3 |

| 2 | 43.1865 | Cholesta-5,7,9(11)-trien-3-ol acetate | 424 | C29H44O2 |

| 3 | 44.2381 | 9-octadecenoic acid (z)-, 2-(acetyloxy)-1-[(acetylox | 440 | C25H44O6 |

| 4 | 55.3084 | Octadecanoic acid, 2-oxo-, methyl ester | 312 | C19H36O3 |

| 5 | 57.3391 | 2,6,6-trimethyl-bicyclo[3.1.1]hept-3-ylamine | 153 | C10H19N |

| 6 | 67.4788 | 9-methyl-z-10-pentadecen-1-ol | 240 | C16H32O |

| 7 | 69.446 | 9,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid, 2-(acetyloxy)-1-[(ace | 436 | C25H40O6 |

| 8 | 71.2874 | 2,6-pyrazinediamine | 110 | C4H6N4 |

| 9 | 81.5278 | 1-bromo-3-(2-bromoethyl)-nonane | 312 | C11H22Br2 |

| 10 | 82.2651 | 2(3h)-furanone, 3-(15-hexadecynylidene)dihydro-4-h | 334 | C21H34O3 |

| 11 | 83.4279 | 3-acetoxydodecane | 228 | C14H28O2 |

| 12 | 91.5287 | Octadecanal, 2-bromo- | 346 | C18H35OBr |

| 13 | 95.4413 | Nonanal | 142 | C9H18O |

| 14 | 97.5356 | Cyclohexanol, 2-methyl-5-(1-methylethyl)-, (1.alpha | 156 | C10H20O |

| 15 | 102.3516 | 6-nitroundec-5-ene | 199 | C11H21O2N |

| 16 | 109.5382 | Hexadecanal | 240 | C16H32O |

| 17 | 111.529 | 7-methyl-z,z-8,10-hexadecadien-1-ol acetate | 294 | C19H34O2 |

| 18 | 126.8301 | 1-hexyl-2-nitrocyclohexane | 213 | C12H23O2N |

| 19 | 138.1874 | Myristic acid vinyl ester | 254 | C16H30O2 |

| 20 | 207.4915 | Cis-9,10-epoxyoctadecan-1-ol | 284 | C18H36O2 |

| Table 7: | In vitro antioxidant activity of A. muricata leaf extracts | |||

| DPPH | FRAP | |||||

| Acetone | Methanol | Ascorbic acid | Acetone | Methanol | Rutin | |

| Percentage of inhibition | mM Fe(II)E/mg | |||||

| Concentration (μg/mL) | ||||||

| 100 | 31.40±4.28e | 25.58±2.03e | 49.61±4.37e | 379.47±2.54e | 154.27±1.22e | 538.01±3.07e |

| 200 | 44.67±2.18d | 28.78±1.77d | 58.72±1.05d | 518.90±5.32d | 260.77±4.62d | 672.15±3.92d |

| 300 | 50.68±2.06c | 44.67±1.10c | 63.18±0.44c | 581.91±3.92c | 382.32±3.66c | 820.12±3.66c |

| 400 | 54.75±1.21b | 47.38±3.03b | 69.19±0.58b | 633.54 ±4.40b | 396.95±2.44b | 858.74±3.73b |

| 500 | 62.40±2.98a | 57.17±5.08a | 71.71±2.44a | 698.17±2.11a | 559.96±1.41a | 955.49±2.44a |

| IC50 (μg/mL) | 105.43±5.94b | 138.42±5.47c | 21.95±9.95a | - | - | - |

| Values represent Mean±Standard Deviation, were significant among the extracts p<0.05 | ||||||

| Table 8: | Antibacterial effect of A. muricata acetone and methanolic leaf extracts | |||

| Extracts | Concentration (μg/mL) | Salmonella typhi | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Escherichia coli | Bacillus subtilis |

| Zone of inhibition (mm) | |||||

| Chloramphenicol (PC) | 10 | 10±0.02b | 12±0.08a | 13±0.3a | 8±0.5cd |

| Acetone (NC) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Acetone extract | 25 | 5±0.03d | 4±0.01b | 3±0.01b | 2±0.01c |

| 50 | 7±0.04c | 4±0.02b | 5±0.01a | 4±0.02b | |

| 75 | 9±0.04a | 6±0.07a | 5±0.06a | 5±0.03a | |

| Methanol (NC) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Methanolic extract | 25 | 1±0.01f | 1±0.01c | 1±0.01c | 0±0.01e |

| 50 | 3±0.02e | 1±0.02c | 1±0.03c | 1±0.02d | |

| 75 | 8±0.02b | 1±0.07c | 2±0.01b | 1±0.03d | |

| Values represent Mean±SE, means significantly different between extracts (p<0.05), PC: Positive control and NC: Negative control | |||||

Antibacterial activity of leaf extracts: Antibacterial activity of acetone and methanol solvent extracts of A. muricata leaves were tested against four different bacterial pathogens. Inhibitory activity of the extracted crude leaf phytocompounds at different concentrations were tested against human bacterial pathogens such as Salmonella typhi, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Bacillus subtilis. Results compared with synthetic chloramphenicol drug (positive control), methanol and acetone was negative control. Acetone leaf extract at 75 μg/mL concentration exhibited stronger antibacterial activity against all human pathogenic bacteria tested (Fig. 6a-d). Acetone leaf extract showed maximum zone of inhibition against Salmonella typhi (9±0.04 mm), followed by Pseudonmonas aeruginosa (6±0.07 mm), Escherichia coli (5±0.06 mm) and Bacillus subtilis (5±0.03 mm), respectively. Whereas, at 75 μg/mL concentration, the methanolic leaf extract exhibited only minimum inhibition activity in all the pathogens tested (Fig. 6e-h).

The methanolic leaf extract exhibited maximum zone of inhibition only against Salmonella typhi (8±0.02 mm). Also, only minimum inhibition zone was exhibited by methanolic crude extract of leaves against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (1±0.07 mm), Escherichia coli (2±0.01 mm) and Bacillus subtilis (1±0.03 mm) (Table 8).

DISCUSSION

Plants play an important role in providing products to help combat various diseases and ailments. The plants in its fresh, dry or in extract form are often utilized in traditional practices as remedy to cure various diseases. The plants belonging to the Annonaceae family serves as potential therapeutic agents because these plants contain acetogenins, alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenes and essential oils. Due to the medicinal value of A. muricata, this plant is being researched by the scientists in recent years9.

A study by Nga et al.16 reported that the phytochemical constituents namely, flavonoids, alkaloids, phenols, terpenoids, tannins, steroids, saponins, glycosides, carbohydrates and proteins were present in different solvent extracts of A. muricata leaves. In our study, the solvents acetone and methanol were used for phytocompound extraction from leaves, because these two solvents will be effective in extracting a wide range of compounds. Methanol is a highly polar solvent, whereas acetone can dissolve both polar and nonpolar substances. In addition, the acetone plant extracts will be more effective in extracting antioxidant and phenolic compounds with antibacterial properties17,18.

The free radicals could be inhibited naturally by the compounds present in A. muricata leaves. Free radicals are compounds having unpaired electrons, which causes diseases such as cancer by searching reactive electron pairs. The harmful effects of the free radicals could be stopped by the plant antioxidant compounds usually containing phenolics and its derivatives19. In our study, initially the antioxidant activity of acetone and methanol leaf extract of A. muricata were analysed using DPPH and FRAP assays. Previous study by Nguyen et al.20 reported that the ethanolic leaf extract of A. muricata possessed antioxidant activity with IC50 value of 20.75±0.28 μg/mL in DPPH assay and 12.84±0.21 μg/mL in ABTS assay. In our study, the acetone leaf extract had shown highest IC50 value of 105.43±5.94 μg/mL in DPPH assay. Also, the acetone extract of A. muricata leaves was found to exhibit highest antioxidant activity with 698.17±2.11 mM Fe(II) equivalents per mg extract. Sujatha et al.21 reported that the chloroform extract of Cassis alata possessed potent antioxidant activity.

In the present study, the extracted phytocompounds from acetone and methanol extracts of A. muricata was analytically characterized using FTIR analysis, and the results revealed different peaks corresponding to various functional groups of metabolites. The acetone extract of leaves showed various functional groups of conjugated anhydride, conjugated alkene, nitro compound, alkane, aromatic ester and sulfonic acid, and the methanolic extract showed functional groups of secondary amines, carboxylic acid, amine salt, esters, α, β-unsaturated ketone, nitro compound, alkane, amine alkyl aryl ether and alkenes. Similarly, Pharmawati and Wrasiati22 analyzed the functional groups present in chloroform: ethanol leaf extract of Enhalus acoroides, which contained alkanes, lipids, hydroxyl groups, fatty acids, secondary amines and benzenoid compounds. The FTIR analysis of the fruit extract of the medicinal plant Ruta graveolens showed the functional groups of alkenes, alkanes and alkyl halides23.

Our study showed that the acetone and methanol leaf extract consists of phenolic and flavonoid compounds namely coumaric acid, catechin, rutin and quercetin at different retention times, which was quantified using HPLC analysis. The HPLC allows precise quantification of each single compound by associating with standard compounds’ retention time. The phenolic compound coumaric acid (57.95 mg/g) were found to be more in the extracts when compared with the flavonoid compounds. Also, Salih et al.24 used HPLC in separation and quantification of phenolic compounds namely gallic acid (9.2 μg/g), quercetin (18.2 μg/g) and tannic acid (29.3 μg/g) in the seeds of Juniperus procera.

In our study, the ESI-MS analysis showed that Octadecane, 1-(ethenyloxy) and 1-hexacosanol were the dominant compounds present in A. muricata leaf acetone extract. Also, the ESI-MS analysis of methanolic leaf extract of A. muricata leaves showed that Cholesta-5,7,9(11)-trien-3-ol acetate was the major compound present in it. Similarly, a previous report by Affes et al.25 studied the presence of phenolics in Aeonium arboreum leaf extracts using ESI-MS/MS analysis. Also, this phytocompound exhibited both antioxidant and antimicrobial activities.

The effect of the phytocompounds present in both acetone and methanolic leaf extract were analysed against disease causing bacterial pathogens. In our study, acetone extract showed maximum inhibitory activity at 75 μg/mL against the pathogens tested namely Salmonella typhi, Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Affes et al.25 also tested the antimicrobial activity of Aeonium arboreum leaf xtracts against different pathogens. Their results suggested that the leaf extracts from 12.5 to 50 μg/mL concentration was found to be effective against the bacteria namely, Listeria ivanovii, Micrococcus luteus, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Settu and Arunachalam26 also studied the phytochemical compound analysis and in vitro pharmacological activities of medicinal plants of Cucurbitaceae family. Similar to our results, the Annona squamosa leaf extracts showed antibacterial activity due to the existence of various pharmacologically important and active compounds27.

CONCLUSION

Hence, current findings states that the acetone extract of A. muricata leaves possess better biological activities when compared with the methanol extracts. These results also support the development of antibacterial drugs with the available bioactive compounds from acetone extract of A. muricata leaves, which could find application in the pharmaceutical industries. In the present study A. muricata leaf extracts possessed various bioactive compounds belonging to the phenolics and flavonoid groups. The compound Octadecane, 1-(ethenyloxy)- was found to be dominant in acetone extract of A. muricata leaves. Hence, the presence of these phytocompounds in leaf crude extract are responsible for the antioxidant activity. In addition, these compounds also contributed to the effective control of disease-causing human pathogens. Therefore, our study suggests the effective utilization of A. muricata leaf extract for antibacterial drug development.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

Despite traditional medicinal use, the phytochemical profile and combined antioxidant–antibacterial potential of Annona muricata leaves remain insufficiently characterised under standardised conditions. In response to rising antibiotic resistance and demand for plant-based antioxidants, this study quantitatively profiles key phytochemicals and evaluates free-radical scavenging and antibacterial activities of leaf extracts. The findings provide scientific validation of traditional claims and support the development of safe, natural therapeutic agents against chronic and drug-resistant infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are thankful to Department of Botany, A.V.V.M Sri Pushpam College (Autonomous), Poondi 613 503, Thanjavur (Dt) Tamil Nadu, for providing laboratory support to carry out the research work.

REFERENCES

- Joshi, B.R., M.M. Hakim and I.C. Patel, 2023. The biological active compounds and biological activities of Desmodium species from Indian region: A review. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci., 12.

- Domingo-Fernández, D., Y. Gadiya, S. Mubeen, T.J. Bollerman and M.D. Healy et al., 2023. Modern drug discovery using ethnobotany: A large-scale cross-cultural analysis of traditional medicine reveals common therapeutic uses. iScience, 26.

- Yuan, H., Q. Ma, L. Ye and G. Piao, 2016. The traditional medicine and modern medicine from natural products. Molecules, 21.

- Abdallah, E.M., B.Y. Alhatlani, R. de Paula Menezes and C.H.G. Martins, 2023. Back to nature: Medicinal plants as promising sources for antibacterial drugs in the post-antibiotic era. Plants, 12.

- Chaughule, R.S. and R.S. Barve, 2024. Role of herbal medicines in the treatment of infectious diseases. Vegetos, 37: 41-51.

- Salm, S., J. Rutz, M. van den Akker, R.A. Blaheta and B.E. Bachmeier, 2023. Current state of research on the clinical benefits of herbal medicines for non-life-threatening ailments. Front. Pharmacol., 14.

- Uchegbu, R.I., K.U. Ukpai, I.C. Iwu and J.N. Akalazu, 2017. Evaluation of the antimicrobial activity and chemical composition of the leaf extract of Annona muricata Linn (Soursop) grown in Eastern Nigeria. Arch. Curr. Res. Int., 7.

- Sokpe, A., M.L.K. Mensah, G.A. Koffuor, K.P. Thomford and R. Arthur et al., 2020. Hypotensive and antihypertensive properties and safety for use of Annona muricata and Persea americana and their combination products. Evidence-Based Complementary Altern. Med., 2020.

- Zubaidi, S.N., H.M. Nani, M.S.A. Kamal, T. Abdul Qayyum and S. Maarof et al., 2023. Annona muricata: Comprehensive review on the ethnomedicinal, phytochemistry, and pharmacological aspects focusing on antidiabetic properties. Life, 13.

- Bennour, N., H. Mighri, H. Eljani, T. Zammouri and A. Akrout, 2020. Effect of solvent evaporation method on phenolic compounds and the antioxidant activity of Moringa oleifera cultivated in Southern Tunisia. S. Afr. J. Bot., 129: 181-190.

- Prakasa, S., V. Srinivasan and G. Packiaraj, 2023. HPLC analysis, phytochemical screening, in-vitro antioxidant and antibacterial activity of Annona muricata L. fruit extracts. Trends Phytochem. Res., 7: 117-126.

- Roesler, R., R.R. Catharino, L.G. Malta, M.N. Eberlin and G. Pastore, 2007. Antioxidant activity of Annona crassiflora: Characterization of major components by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Food Chem., 104: 1048-1054.

- Blois, M.S., 1958. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature, 181: 1199-1200.

- Pulido, R., L. Bravo and F. Saura-Calixto, 2000. Antioxidant activity of dietary polyphenols as determined by a modified ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay. J. Agric. Food Chem., 48: 3396-3402.

- Rawat, P., V. Chauhan, J. Chaudhary, C. Singh and N. Chauhan, 2022. Antibacterial, antioxidant, and phytochemical analysis of Piper longum fruit extracts against multi-drug resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella strains in vitro. J. Appl. Nat. Sci., 14: 1225-1239.

- Nga, N., G. Nchinda, L. Mahi, P.B. Figuei, J.M.M. Mvondo, B. Sagnia and D. Adiogo, 2019. Phytochemical screening and evaluation of antioxidant power of hydro-ethanolic and aqueous leaves extracts of Annona muricata Linn (Soursop). Health Sci. Dis., 20: 29-33.

- Altemimi, A., N. Lakhssassi, A. Baharlouei, D.G. Watson and D.A. Lightfoot, 2017. Phytochemicals: Extraction, isolation, and identification of bioactive compounds from plant extracts. Plants, 6.

- Tourabi, M., A. Metouekel, A.E.L. ghouizi, M. Jeddi and G. Nouioura et al., 2023. Efficacy of various extracting solvents on phytochemical composition, and biological properties of Mentha longifolia L. leaf extracts. Sci. Rep., 13.

- Hartati, R., F. Rompis, H. Pramastya and I. Fidrianny, 2024. Optimization of antioxidant activity of soursop (Annona muricata L.) leaf extract using response surface methodology. Biomed. Rep., 21.

- Nguyen, M.T., V.T. Nguyen, L.V. Minh, L.H. Trieu and M.H. Cang et al., 2020. Determination of the phytochemical screening, total polyphenols, flavonoids content, and antioxidant activity of soursop leaves (Annona muricata Linn.). IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng., 736.

- Sujatha, J., S. Asokan and S. Rajeshkumar, 2018. Phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of chloroform extract of Cassis alata. Res. J. Pharm. Technol., 11: 439-444.

- Pharmawati, M. and L.P. Wrasiati, 2020. Phytochemical screening and FTIR spectroscopy on crude extract from Enhalus acoroides leaves. Malays. J. Anal. Sci., 24: 70-77.

- Al-Shareefi, E., A.H. Abdal Sahib and I.H. Hameed, 2019. Phytochemical screening by FTIR spectroscopic analysis and anti-fungal activity of fruit extract of selected medicinal plant of Ruta graveolens. Indian J. Public Health Res. Dev., 10: 994-999.

- Salih, A.M., F. Al-Qurainy, M. Nadeem, M. Tarroum and S. Khan et al., 2021. Optimization method for phenolic compounds extraction from medicinal plant (Juniperus procera) and phytochemicals screening. Molecules, 26.

- Affes, S., Amer Ben Younes, D. Frikha, N. Allouche, M. Treilhou, N. Tene and R. Mezghani-Jarraya, 2021. ESI-MS/MS analysis of phenolic compounds from Aeonium arboreum leaf extracts and evaluation of their antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Molecules, 26.

- Settu, S. and S. Arunachalam, 2019. Comparison of phytochemical analysis and in vitro pharmacological activities of most commonly available medicinal plants belonging to the Cucurbitaceae family. Res. J. Pharm. Technol., 12: 1541-1546.

- Kumar, M., S. Changan, M. Tomar, U. Prajapati and V. Saurabh et al., 2021. Custard apple (Annona squamosa L.) leaves: Nutritional composition, phytochemical profile, and health-promoting biological activities. Biomolecules, 11.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Prakasa,

S., Srinivasan,

V., Packiaraj,

G. (2026). Phytochemical Profiling and in vitro Assessment of Annona muricata L. Leaf Extracts for Antioxidant and Antibacterial Propertie. Research Journal of Medicinal Plants, 20(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3923/rjmp.2026.01.14

ACS Style

Prakasa,

S.; Srinivasan,

V.; Packiaraj,

G. Phytochemical Profiling and in vitro Assessment of Annona muricata L. Leaf Extracts for Antioxidant and Antibacterial Propertie. Res. J. Med. Plants 2026, 20, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3923/rjmp.2026.01.14

AMA Style

Prakasa

S, Srinivasan

V, Packiaraj

G. Phytochemical Profiling and in vitro Assessment of Annona muricata L. Leaf Extracts for Antioxidant and Antibacterial Propertie. Research Journal of Medicinal Plants. 2026; 20(1): 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3923/rjmp.2026.01.14

Chicago/Turabian Style

Prakasa, Sathiyavani, Vasantha Srinivasan, and Gurusaravanan Packiaraj.

2026. "Phytochemical Profiling and in vitro Assessment of Annona muricata L. Leaf Extracts for Antioxidant and Antibacterial Propertie" Research Journal of Medicinal Plants 20, no. 1: 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3923/rjmp.2026.01.14

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.